“In the loving calm of your arms”

November 13, 2016 § 2 Comments

Embrace me, my sweet embraceable you

Embrace me, you irreplaceable you

just one look at you my heart grew tipsy in me

You and you alone bring out the gypsy in me

(from “Embraceable You,” lyrics by George and Ira Gershwin)

There is something so fundamental, so primitive, so elemental about an embrace that it almost seems pointless to discuss it. It is something we do naturally, effortlessly from birth to death, something that is considered essential to healthy human development. Studies have shown that a lack of such physical contact in early childhood can lead to psychological problems later in life, including an inability to form emotional bonds. In that sense it can be considered one of the defining features of being human (although similar forms of nurturing behavior seem to be prevalent in all mammals).

I came across an interesting piece at the blog Tango Therapist recently about the significance of touch and what it can communicate. The author quotes a recent study about the ways in which touch can convey quite distinct emotions, something I had never considered. The extremes are obvious, since they range anywhere from a caress to a slap, but it’s the in-between stuff that’s interesting. Commenting on the article, the author writes “The emotions included: anger, fear, happiness, sadness, disgust, surprise, embarrassment, envy, pride, love, gratitude, and sympathy. Men were just as good as ‘decoders’ as women in the experiments carried out in both Spain and America. Those trying to portray the various emotions were not told what to do, but similarities of touching behaviors emerged, such as stroking to show love, sadness, envy or sympathy.” If accurate, we can conclude from this that forms of touch, a touch of the hand even, can communicate more than the simple fact of our presence. They can alert us to distinct moods and feelings, often quite complex, which are integral, indeed essential, to everyday life.

The embrace, or abrazzo, is one of the critical elements of tango, some would say it’s a defining feature of the dance. The close proximity it affords enables dancers to convey not only changes of direction or intention but subtle shades of emotion as well, and it is the latter that is often praised as one of tango’s enduring benefits. Its clearest expression is found in the so-called milonguero style of tango popularized by dancers and teachers such as Susana Miller, Monica Paz, and their followers. It’s been described elsewhere, perhaps more accurately, as tango “estilo del centro” because its practitioners were found largely in the dance halls and clubs located in central Buenos Aires. (For an in-depth analysis of tango styles, see Tango Voice.)

The traditional abrazzo is one of the great virtues of tango. While all social dances help break down the distance between self and other, it is in the tango of the embrace that we experience this so forcefully because of its centrality. It focuses our attention on our partner rather than the surrounding crowd and allows us to experience the urgency of communicating emotions—our own, those expressed by the music—through movement and directly through immediate physical contact. It is this directedness that I have always found so compelling about tango, the need to focus on someone else, the need to channel the music through ourselves and our partner. This act of sharing, this emphasis on the integrity of the couple is one of the most compelling aspects of the dance. For, in forcing us to turn our attention to someone other than ourselves—our skill, our technique, our ability—we come a little closer to minimizing our isolation, our sense of being a disconnected, autonomous entity whose struggle is our own.

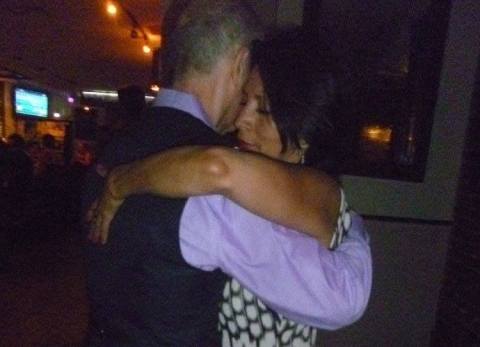

We can see this sense of inwardness and calm reflected in the many photographs of social dancers, and which seem to express the feelings of peace and serenity associated with contemplation or meditation, or deep relaxation. The embrace of tango is the visual expression of a shared secret, which is why it is largely silent, undisclosed to the outside world. For a culture, it also tells us something about how men relate to women and women to men. Characteristically, we never find it in performers (which is to be expected) or proponents of alternative forms of tango, such as tango nuevo. This stream of tango flows largely, but certainly not exclusively, from dancers such as Gustavo Naveira and his students, although precedents can be found in earlier forms of tango—Virulazo, being one example. The form of tango promulgated by Naveira and his followers is frequently danced with the bodies at arm’s length to allow for more complicated movements unsuitable to a crowded ronda but very much at home on stage. The separation allows the bodies of both dancers to be seen clearly by the audience and allows for individual self-expression.

A line can be drawn from Naveira and his followers to today’s peripatetic tango performers, who specialize in exhibitions and stage performances. Although not all performers are practitioners of tango nuevo, such highly choreographed exhibitions frequently entail movements that have little to do with the traditional tango de salon that has evolved over the course of the twentieth century.

Practitioners and teachers often speak of tango as either “open embrace” or “close embrace,” the former being typical of nuevo styles of dancing. This is a misnomer, however. An embrace is by definition something that joins two bodies in a reciprocal movement. The separation characteristic of tango nuevo is not an embrace at all, but simply a dance hold, a way of creating a frame for movement. It can be fun to dance and lovely to watch in a skillful couple, but it is something quite different from the traditional “tango of the center” in its form and intent.

Many have written about, and lamented, the way tango has developed in North America (and elsewhere) and how it has diverged from its roots to accommodate the influence of stage tango, performance tango, and nuevo tango. (For a discussion of this phenomenon, see Tango Voice.) And, of course, the ballroom dance known as American “tango” bears little resemblance to its southern progenitor. Indeed, it is hard to imagine tango evolving in the Protestant north at all, with its Calvinist severity and guilt, its suspicion of the body as nothing more than an impure vessel in need of cleansing. A propos of this forked development, there is an interesting comment made by Jo Baim in her book on tango. Speaking of the growth of the dance in North America between roughly 1910 and 1925, she writes:

Naturally, any dance master who included a written description of the tango wanted his or her students to accept it, so many writers included assurances that the tango was suitable for the ballroom and that its toned-down style had been purged of all objectionable South American elements. (Jo Baim, Tango: The Creation of a Cultural Icon.)

We find echoes of this even today in the prevalence of nuevo and “open” tango styles in North America, a marked contrast to the way the tango has been danced at traditional milongas in Buenos Aires. Tango—the music and the dance—originated in Buenos Aires and its environs (more specifically, the area around the Rio Plata), a southern culture in which physical contact was, and is, commonplace. Once it had become established as a legitimate form of social dance, the intimacy found in tango could be seen as an extension of everyday life, nothing shameful, nothing strange, nothing illicit. For this we should be grateful.

“The gesture of the amorous embrace seems to fulfill, for a time, the subject’s dream of total union with the loved being.”

(from Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, translated by Richard Howard).

“Hell is having arms but no one to embrace”

Jon Kalman Stefansson, Heaven and Hell.

Open embrace = thinking tango

Close embrace = feeling tango

We all need daily hugs, and tango provides them.

LikeLike

[…] I can relate this to something I had written earlier about the abrazo in tango and its centrality [“In the loving calm of your arms”]. All of the dancers interviewed by Paz are old-school milongueros and dance within that tradition […]

LikeLike