Time’s Arrow

July 14, 2024 § Leave a comment

“Time will always be with us.”1

It has always been about time. Something we don’t think about until it’s too late. Something of which there is either too much or too little. Often treated as a commodity (time = money), time has never been adequately defined or identified. You could think of it as a useful convention, a convenience, but one so deeply embedded in our lives that it is hard to imagine life without it. Was it so always and everywhere? Even today its dominance is not felt uniformly across all aspects of life.

Humankind has had dreams of manipulating time for almost as long as we have had fiction. H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) is one of the earliest and arguably best known treatments of the topic but it is far from the last word on the subject. Since then, novels and films have been trying to unravel time as if it were a spool of thread that could be wound and unwound at will, a continuity that retained every aspect of a previous existence in technicolor detail. Cinema is replete with undisclosed technologies that can catapult time travelers backwards and forwards across great arcs of time. Arrival, 12 Monkeys, Looper, The Terminator, Lucy, Interstellar, and, of course, La Jetée—these are only some of the best known works in the category. All of them attempt to turn travel from the future back to the past into cinematic reality or play with the order of time and its consequences in a malleable “present.” None strive for scientific accuracy, but their attraction is not how well they reflect current physical theory but their ability to stimulate us to question the absoluteness of time’s irreversibility. The reality, of course, is quite different.

As a variable in a mechanical system, time, like other variables, can assume both positive and negative values. In such a system there is no distinction between moving forward and backward in time other than the sign of that variable, which provides a sense of direction. A mechanical process can unfold in one time direction just as easily as it can in the other. None of the equations that describe such processes distinguish between what we would consider “past” and “future,” and this holds true at both macroscopic and microscopic scales. For science, the only substance that distinguishes temporal direction, time’s advance, is the presence of heat, a form of energy. As Hans Christian Von Baeyer writes in Maxwell’s Demon, “Newton’s and Einstein’s laws of mechanics, Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism, the quantum theory of atoms, and even, with one rather insignificant exception, the modern descriptions of elementary particles in terms of quarks are time-symmetric.”2

If we dig deeper, down to the level of subatomic processes, where quantum effects occur and probabilistic laws are paramount, time is of little consequence. The world of elementary particles, the building blocks upon which everything in this universe is constructed, is unburdened by the concept of time. In The Order of Time, theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli writes: “[Time] is not directional: the difference between past and future does not exist in the elementary equations of the world; its orientation is merely a contingent aspect that appears when we look at things and neglect the details.”3

Consequently, and surprisingly, for all its usefulness, time turns out not to be an intrinsic physical property at all like mass, or length, or electrical charge, it is something far more elusive. And within such systems and at such physical scales, notions of past and future cease to be relevant.

“We often say that cause precedes effect and yet, in the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between ‘cause’ and ‘effect.’ There are regularities, represented by what we call physical laws, that link events of different times, but they are symmetric between future and past. In a microscopic description, there can be no sense in which the past is different from the future.”4

And yet all of us intuitively feel time’s passage and know from direct observation of the world around us that living things develop in one direction only—from gestation to growth to extinction. Whether a seed that turns into a sapling and then a mature tree, an insect that develops from a larval state to maturity, or a mammal that starts life as a newborn and passes through the various stages of its life, all such processes appear to be governed by time.

Aside from the results of personal observation and our intuitive understanding of aging, of the directedness of biological processes, that the concept of time is unidirectional and irreversible is based largely on the discovery of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. It posits that entropy, the state of disorder—or randomness—of a closed system, can only increase in moving from one state to another. Or to put it in more immediately thermodynamic terms, in such a closed system, heat can never spontaneously flow from a cold body to a hot body. In this representation time is assimilated to entropy and entropy points only one way—toward its inevitable increase. On a cosmic scale, this is sometimes referred to as the ”heat death” of the universe. As Rovelli points out, “[The Second Law of Thermodynamics] is the only basic law of physics that distinguishes the past from the future.”5

We tend to think of time as a sequence of events, a continuous flow from one moment to the next toward an unknown future state. It is a form of linear progression along a path from yesterday to tomorrow. Before the advent of modern timekeeping devices, time was measured indirectly, notably by the measurement of distance in some form. (Sundials in ancient Egypt measured the length and direction of the Sun’s shadow.) How long does it take the Earth to rotate around its axis? How long for the Earth to revolve around the Sun? At some point in human development, it became useful to assign values to repetitive, periodic motions—hours, days, weeks, years. Such knowledge—the ability to divide nonbiological processes into regular increments—helped organize everyday life. It also allowed humans to plan for the future. These are functional definitions, cyclical or linear, that turn time into something discrete and quantifiable. Not being a physical value, time cannot be weighed or measured or captured like a pound of grain or the wavelength of visible light. It is not a thing, it is a concept and so it must be approached circumspectly.

It would be interesting to speculate on the nature of human experience before the invention of timekeeping, even before the notion of measurable periods of time. Certainly, when sedentary cultures and early agricultural communities came into being (approximately 12,000 years ago), there had to have been a clear awareness of cyclical patterns in nature—the revolution of the sun over the course of the day, the division between nighttime and daytime, the changes in the seasons—or agriculture would have been impossible. Even earlier members of the sapiens species, hunter-gatherer societies, must have had some notion of diurnal motion as well as recurring seasonal changes. A primitive sense of the cyclical nature of things would have been needed, even if it was associated only with the movements of wild animals or the appearance of specific plants in certain locations. Such cycles would have been incorporated into everyday life as a form of routine—sleeping, waking, hunting, periods of abundance or scarcity, occasionally migration. There need not have been a method of physically recording such regularities for at least an amorphous concept of time to have existed.

But before that? Before that speculation becomes riskier. Did the earliest humans have a sense of cyclical regularity in nature that we would associate with the concept of time, a sense of its directionality? It is believed that early sapiens already had the capacity for symbolic or abstract thought. The time between the earliest appearance of modern humans—roughly 300,000 years ago (although that figure is not universally accepted)—and the present day is not that long in terms of evolutionary development. This implies that the brains of the earliest Homo sapiens were likely very similar to our own in terms of size and capability. If so, their capacity for abstract thought would have been similar to our own even if not yet fully developed. And one had to have the ability to think abstractly to posit a concept such as time and use it as an organizing principle in one’s life.

Nonetheless, I can’t help but wonder if life back then, when modern humans were first coming onto the scene, wasn’t a kind of eternal present, day shading into night, night into day, one day into the next, with no way to describe temporal movement or divide life into distinct phases of existence—a known past to which one had access and an unknown future forever foreclosed. Moreover, it is difficult to conceive of something as sophisticated as time as a measurable quantity without the use of language and the ability to manipulate concepts. And about the origins of language we are largely in the dark.

Living alone or in very small groups, would the exigencies of daily existence have allowed early humans to develop a clear sense of temporal direction? If not, if life were one continuous present, it would have been time-less. Life would have lacked any concrete attachment to a past (individual or communal) or sense of a possible future that could be acted upon in the present. But it would also have been without the fear that such a future portends, not just uncertainty but the knowledge of life’s inevitable end at some future point in time. I do not mean to imply that life on Earth was a kind of untroubled paradise. Obviously, life was precarious and lifespans were short; the threat of death was all around and immediate. But it is not inconceivable that the concept of a present, a now, as a discrete moment in a temporal continuum, one that slipped into an anxious future that can only end one way, would have been alien to our earliest ancestors. The lives of early humans were threatened on many fronts but they were at least free of the existential dread that time-bound humanity later experienced.

I have always thought of early childhood in this way. Time doesn’t seem to exist for the very young child—there is no past, no future, only a present filled with needs and experiences. I’m not sure at what point or at what age children begin to “understand” time, but it is clearly something that must be taught—it is part of becoming a functioning member of a community. And if we don’t learn it at home, we learn it at school. The big hand and the little hand move inexorably around the day’s circle. From that moment on, we are chained to the concept of time’s passing, of a directed future and all it entails as socially responsible adults.

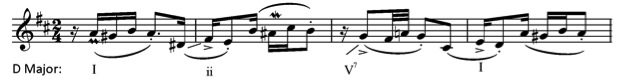

More relevant to my purpose, time is also diffracted through music, which is essentially an orderly unfolding of sound over time. When we speak of time in music, the most obvious association is with tempo and rhythm. Musical tempo—tempus, tempo, temps, tiempo—is literally time. When characterized by the number of beats per minute, it serves as a kind of clock: the greater the number of beats we squeeze into a given unit of time, the faster the music. Musical structure—the musical score, the notes on a page, time signatures—in one sense represents movement toward an end point. Though we may not often think explicitly of musical structure in tango—rhythm and melodic phrasing primarily—it is reflected in the way we move. There is, or should be, a direct correlation between musical structure (for a given song by a given orchestra) and physical interpretation. Musical time, syncopation, rhythm, melody—these are the elements reflected visually and kinesthetically in the dance. Of course, such a relationship holds true to some extent for all dance forms, social and otherwise. In social tango, which is, after all, an improvisational dance, musical structure guides our individual vocabulary in the moment: when we move, how we move, when we pause. Such visual manifestations are what distinguish one individual from another; they reflect the “personality” of the dancer.

The ronda itself (the “round”—not round as in circular but a turning around or about something, from the verb rondar) reflects the motion of the dancers as they circulate around the floor. Basically, it is nothing more than the line of dance. On an orderly floor, it moves in a counterclockwise circle, continuously revolving until it stops, that is, until the music ends. The ronda is also a reflection of musical time, a kind of clock, although one that moves backward as time moves forward. A visual representation of moving backward in time.

“So death and time are interchangeable. Death is another name for time. And that will be my salvation. At least for today.”6

But it is the absence of time I am trying to express, the absence of a sense of its passage, its forward movement, its associations. This sounds contradictory because dancers are always moving to a musical beat, explicit or implicit. We are always (mostly) in motion around the floor, marking time so to speak. However, something else transpires when all the elements come together in just the right way. And that something is the temporary cessation of time’s passage.

This may be one of tango’s unheralded benefits, perhaps its greatest. Dancers often speak about connection, about passion, about the healing power of the dance, its restorative capacity. Such lofty sentiments are legitimate attempts at describing a complex psychological state. Although not well understood, tango’s benefits have been shown to be real both physically and emotionally.7 Yet, we also experience something more, something that is rarely mentioned: the ability to stop time, to freeze its passage even briefly. Such moments may be transient, but they introduce an element of possibility into the present. An element of uncertainty as well, for in such a state we begin to see the world in a subjunctive mood, where the future isn’t foreclosed or defined in advance. It is a horizon filled with potential. Of course, this is a lot to expect from a dance, but even shifting the focus away from ourselves for the duration of a tango is a way to defer the inevitable and expand the present.

There would be little anxiety about the future, that unknown shore, if not for the inevitability of death for all living things. Such sentiments arise not only from social conditioning but from observation and personal experience. And this brings us back to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the law of entropy, “time’s arrow,” which describes such a fate, although over immeasurably long periods. But entropy is abstract and its time scales, at least when speaking of the universe, are beyond our comprehension. Biological life, however, is concrete, immediate, and temporally limited. No living thing is exempt from time’s grip. But if we can stop time, we can escape the sense of an impending future, the anxiety of inevitability. So for those brief moments in tango’s embrace, when everything comes together and the world falls away, we become one and we are timeless.

1. Etel Adnan, Paris, When It’s Naked (Post-Apollo Press, 1993), 109.

2. Hans Christian Von Baeyer, Maxwell’s Demon (Random House, 1998).

3. Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time (Riverhead Books, 2018), 91.

4. Ibid., 33.

5. Ibid., 24.

6. Adnan, 112.

7. See, for example, Julie Sedivy, “Can Another Body Be Seen as an Extension of Your Own?” Scientific American, January 30, 2016.