Maxima Minima

January 23, 2018 § Leave a comment

A literary theorist, Takayoshi Ishiwari, relates the growth of maximalism with the rise of epistemological uncertainty, a condition that hampers our ability to distinguish between authenticity and inauthenticity. In the attempt to compensate for doubt and uncertainty, maximalism attempts to pack as much as possible of the contemporary world into a work of literature. The reasoning seems to be that by doing so, there is at least the possibility of being or saying something authentic through a process of comprehensive inclusion. Embracing excess is a means of compensating for our anxiety about what we do not and may not ever know.

As the embodiment of surfeit, maximalism in literature is typical of many modern and postmodern novels—Thomas Pynchon, for example, or Don De Lillo’s Underworld. When compared to minimalism, it is Joyce and Proust (was there ever a greater maximalist?) rather than Beckett and Duras.

And in a paper titled “Defining Maximalism: Understanding Minimalism” by Patrick Templeton, maximalism is defined as “an extreme visual incoherence . . . to the point that nothing can be isolated as a discrete thing, thus preventing the recognition of a whole.” (Templeton, Patrick, “Defining Maximalism: Understanding Minimalism” (2013). http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/3.) This inability to see the world as whole or to encompass all aspects of a problem at once could be said to be part of the modern condition. Ironically, in the fine arts at least, the maximalist stance is not restricted to the contemporary world, as a glance at the work of Breughel or Bosch will attest. Anxiety, post-Freud, may typify the modern era but it is not unique to it.

Notwithstanding minimalism’s critical success and widespread adoption by the art market, it was dismissed by the public, who scoffed at the notion that a “monochromatic” painting (often built up of layers of color) could represent or embody anything, and certainly not anything of value or substance. Even today, the response to painters like Mark Rothko or Clyfford Still is often one of perplexity or suspicion. The maximalist stance of much of postmodern and contemporary painting has fared somewhat better, largely because of its extravagance and frequent adoption of the motifs and methods of “low culture” (graffiti, cartoon characters, pop cultural motifs), but essentially because of its exuberant excess, its attempt to pack as much as possible into a single work. (An installation of work by Kenny Scharf would be a good example.) And because it makes fewer demands on the viewer.

While these theorists are talking primarily about literature and the fine arts, their definitions could also be applied to tango. Unlike “salon” tango or just about any form of social tango, performance seeks to wow the audience with technique, agility, and choreographic innovation. It packs a great deal of movement and variation into a three-minute dance, and one is often struck by the almost desperate attempt to impress the spectator and surpass previous performances (there is a thriving market in tango competitions). Yet, this kind of maximalist surfeit evinces both insecurity and uncertainty, which we don’t find in exhibitions by older milongueros or on the floor of a traditional milonga. In this case, the maximalist stance is characterized by the need to include as much as possible in a social dance that has always made use of relatively simple forms of movement.

So, maximalism in tango, as a first attempt at a definition, would be the apparent necessity of dancers—primarily, but not exclusively, performers—to fill a dance with as many steps, as much movement, as much drama, as many choreographic elements as possible. Because it is directed at an audience and not meant to be danced on a crowded floor surrounded by other dancers, the use of space is different and the amount of energy applied greatly amplified. There are countless examples of this type of dancing on video.

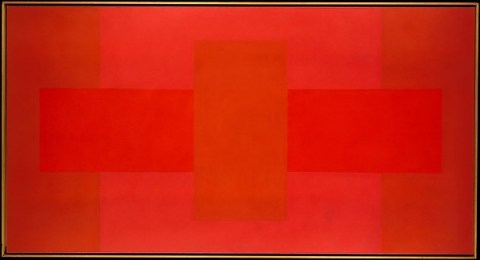

Ad Reinhardt – Metropolitan Museum of Art

While minimalism is well-known in painting, and represented by some of the most famous names in twentieth-century art, where do we find it in tango? Is there a Rothko or Ad Reinhardt of tango? As a possible starting point, I’d suggest looking at some of the videos of Alberto Dassieu, perhaps the most contained, the least overtly emphatic dancer to have appeared on video.

or

One could find many more examples of similar exhibition tangos by well-known dancers and milongueros, although a well-run milonga might provide better examples of contained and inner-directed dancing. The belief that less is more runs through various strains of minimilism in the fine arts, although it is a movement whose time has come and mostly gone (we still find examples of minimalism or post-minimalism in contemporary art, of course). As in painting, there are no hard and fast rules about how to create. We all follow our own path, so to speak. It’s more a question of how a personal style evolves, one that expresses our feelings, emotions, and creativity. But as beginners, who or what do we emulate? Do we consciously choose role models on which to base our development? Are there even role models on whom to draw for inspiration or matters of style? Technique can be learned, but tango is about much more than technique. It’s largely about what happens when we can forget about technique and focus on the music. I believe it was Gavito who said that tango is what happens between the steps. It’s a beautiful concept because it de-emphasizes the most obvious and external elements of tango—footwork, embellishments, speed—and focuses on the relationship between two dancers and the music. It’s a concept that’s easily overlooked because frequently overshadowed or drowned out by the flash and clamor of performance tango, with its instant appeal. The “problem” with tango in its quieter modes is that it requires more effort on the part of the viewer to perceive and the dancer to enact; it requires the ability to stop, to listen, to wait, to breathe.

The case of Gavito

What about Gavito, then? Is he a maximalist or a minimalist? He’s a little of both, I think, rather than a pure expression of either. He’s a maximalist in the sense that his dancing is both extremely stylized and highly dramatic (his stage performances demonstrate this), and epitomizes the tragic and romantic elements of tango. Though unstated, Gavito’s approach makes great use of the myths of tango, its clouded past, public perceptions of its social importance and unruly pedigree, and, frequently, its steamy eroticism. But he is a minimalist in the sense that his dance is often reduced to essentials in terms of its gestures and movement, and seemingly inner directed or, rather, directed entirely at his partner. The energy is centripetal, towards the couple, but showy enough to appeal to an audience.

Please leave a reply.